Myth: ‘Eating less and moving more is the best way to lose weight.’

‘Eat less, move more’ is often thought of as the foundation of weight loss. It sounds straightforward and manageable. Unfortunately, weight loss is a bit more complicated than that.

Many factors can influence weight loss, such as your genetics, food environment, exercise levels, whether you have any underlying medical conditions, psychological health, and nutrition education.

So, this guide will bust the myth that the ‘eat less, move more’ is the approach to losing weight and unpacks the real science of weight loss.

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

What is ‘eat less, move more’?

The basic idea behind ‘eat less, move more’ is that body fat is purely a result of excess energy. By this theory, we will lose weight if we take in less energy than we’re using up. Eating fewer calories than we’re using up is called being in a calorie deficit.

From a biological point of view, it makes sense that if we have more energy than we need, our bodies will store that energy. The excess energy is stored as glycogen in your muscles or fat.

This idea assumes that all calories are digested the same way and have similar effects on our body. However, this is not the case.

Proteins (e.g. eggs or chicken) and fats (e.g. avocado or olive oil) do not have a big effect on our blood glucose levels, whereas carbohydrates (e.g. bread or pasta) do.

Eating excessive amounts of carbs increases our blood glucose levels and causes insulin spikes. Insulin is one of the main hormones controlling our blood sugar levels and promoting fat storage.

Key Points:

- Eating less and moving more means restricting your calories and exercising more.

- This approach to weight loss is based on the idea that body fat is excess energy and all calories have equal health benefits.

Does eating less and moving more work?

Evidence suggests that following a calorie-restricted diet results in some weight loss in the short term.

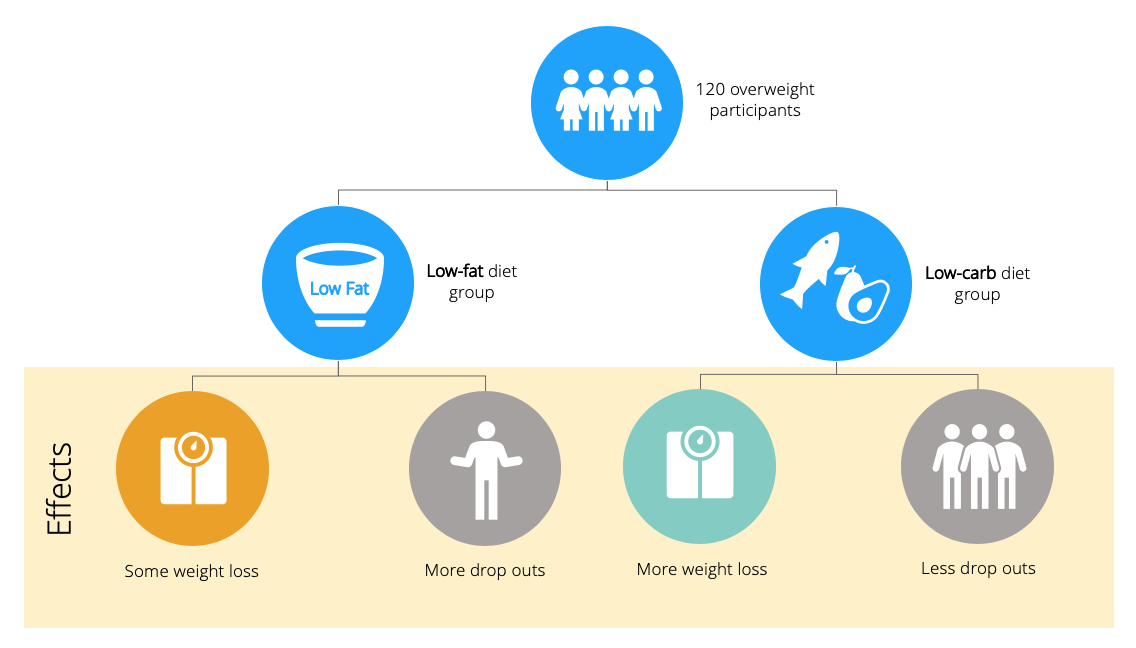

One study demonstrated that putting participants into a calorie deficit for eight weeks resulted in weight loss. This effect was seen regardless of whether participants were placed on a low-fat or low-carbohydrate diet.

However, this study was only eight weeks long, and the participants’ diet was carefully controlled. In real life, achieving and maintaining a calorie deficit is very complicated and time-consuming.

In a slightly longer study that lasted six months, a low-carb diet resulted in more weight loss than a low-fat, calorie-restricted diet.

The low-carb group were allowed unlimited meat, eggs, and dairy products, all relatively high-calorie foods.

There are a few potential explanations for the results of this study. Some evidence suggests that when we dramatically restrict our food intake, our bodies have an evolutionary response of increasing the hormones responsible for appetite. This makes us feel hungrier and increases the chances of us eating more.

Another potential explanation is that the participants’ mindset and environment influenced their food choices.

If we’re feeling deprived and restricted (e.g. on a low-calorie diet), we’re much more likely to lose motivation and be influenced by foods in our environment.

Often if we feel hungry and deny certain foods, we will most likely accept a doughnut when offered one.

This highlights that weight loss is as simple as ‘eat less and move more’ and doesn’t account for mindset or environment influencing food choices.

Participants in this study were given regular dietary advice, possibly more reflective of dieting in the real world rather than in a clinical setting.

By the end of the study, fewer participants in the low-carb group dropped out compared with the calorie-restricted group. This suggests that the low-carb diet was easier to stick to.

Key points:

- Eating less and moving more (i.e. achieving a calorie deficit) is effective for weight loss in the short term.

- In the long term, low-calorie diets are difficult to stick to and might leave you feeling hungry.

- ‘Eating less, move more’ implies that weight loss is solely about diet and exercise, but ignores the importance of mindset and environment influencing food choices.

Is it healthy to simply ‘eat less, move more’?

Even if you are looking for a short-term fix and want to restrict your calories, is that approach healthy?

Evidence suggests that dramatically restricting your calorie intake doesn’t account for the fact that not all calories provide equal health benefits and can foster an unhealthy relationship with food.

Not all calories are equal

The evidence suggests that not all calories are the same and shouldn’t be considered equal energy sources.

To illustrate, 500 calories of sweets and biscuits don’t provide the same nutritional benefit as 500 calories of chicken and vegetables.

Eating too many refined carbohydrates, for example, can lead to high blood sugar and promote fat storage. In the short term, blood sugar spikes can leave you low on energy and increase your cravings for sugary foods.

In the long term, consistently high blood sugar levels can lead to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

On top of this, protein and fat are digested more slowly than carbs, which leaves us feeling fuller for longer. This reduces the chances of snacking and feeling hungry or deprived.

Examples of refined carbohydrates include white bread, white rice, and cakes. It’s not necessary to eliminate carbs, but reducing your carb intake and choosing high-fibre, complex carbs when you eat them can help with weight loss.

Examples of high-fibre, complex carbs include oats, sweet potato, and quinoa. A good practical tip is to have one carb-free meal daily. Trying a new low-carb recipe each week is a simple, fun way to achieve this goal.

Key points:

- Not all calories provide equal health benefits.

- Eating too many refined carbohydrates can leave you feeling low on energy, increase cravings, and lead to insulin resistance in the long-term.

An unhealthy relationship with food

Obsessing over calorie counting can harbour an unhealthy relationship with food.

Seeing food merely as ‘calories’ can make us lose touch with our natural hunger and fullness cues, as we are too focused on the numbers. This leads to us eating less mindfully.

Mindful eating is an essential tool to help us become more aware of what we’re eating, how much we’re eating, and why we’re eating it.

In the long run, this can help us control our portion sizes and caloric intake and stay in tune with our body’s needs.

To practice mindful eating, try eating without distractions (e.g. away from the tv), engaging all your senses while you eat, and taking the time to eat slowly.

Usually, people find that they need to eat less when they are in tune with their natural hunger signals.

Focusing on restricting calories can also take all the enjoyment out of food. Worrying about numbers instead of enjoying a meal out with friends can become tiresome and unenjoyable. Food is meant to be enjoyed as well as to fuel our bodies.

On top of this, if we’re experiencing more cravings for junk food and feeling hungry, we will likely not stick to our plan, leading to weight gain.

Restricting calories can lead to guilt associated with going over your ‘calorie intake’ for a particular day. Guilt is one of the main reasons people get stuck in an unhealthy cycle of binge behaviours.

Key points:

- Calorie-counting makes us lose touch with our natural hunger cues and can foster an unhealthy relationship with food.

- Obsessing over numbers leads to us eating less mindfully and takes all the enjoyment out of food.

Does moving more lead to weight loss?

The ‘eat less, move more’ model suggests that the benefit of exercise is that it uses up calories and helps you achieve a calorie deficit.

Physical activity doesn’t inherently lead to weight loss, but certain types of exercise can aid weight loss.

From a practical perspective, it would take an extremely long time to use up the calories from the foods we eat by exercising.

For example, a normal-sized Cadbury’s dairy milk chocolate bar contains 240 calories.

For an average cardio workout in the gym, it could take 30 mins – 2 hours to use up this many calories, depending on your size and the type of exercise you are doing.

This highlights the impracticality of suggesting that we should exercise more to achieve a calorie deficit.

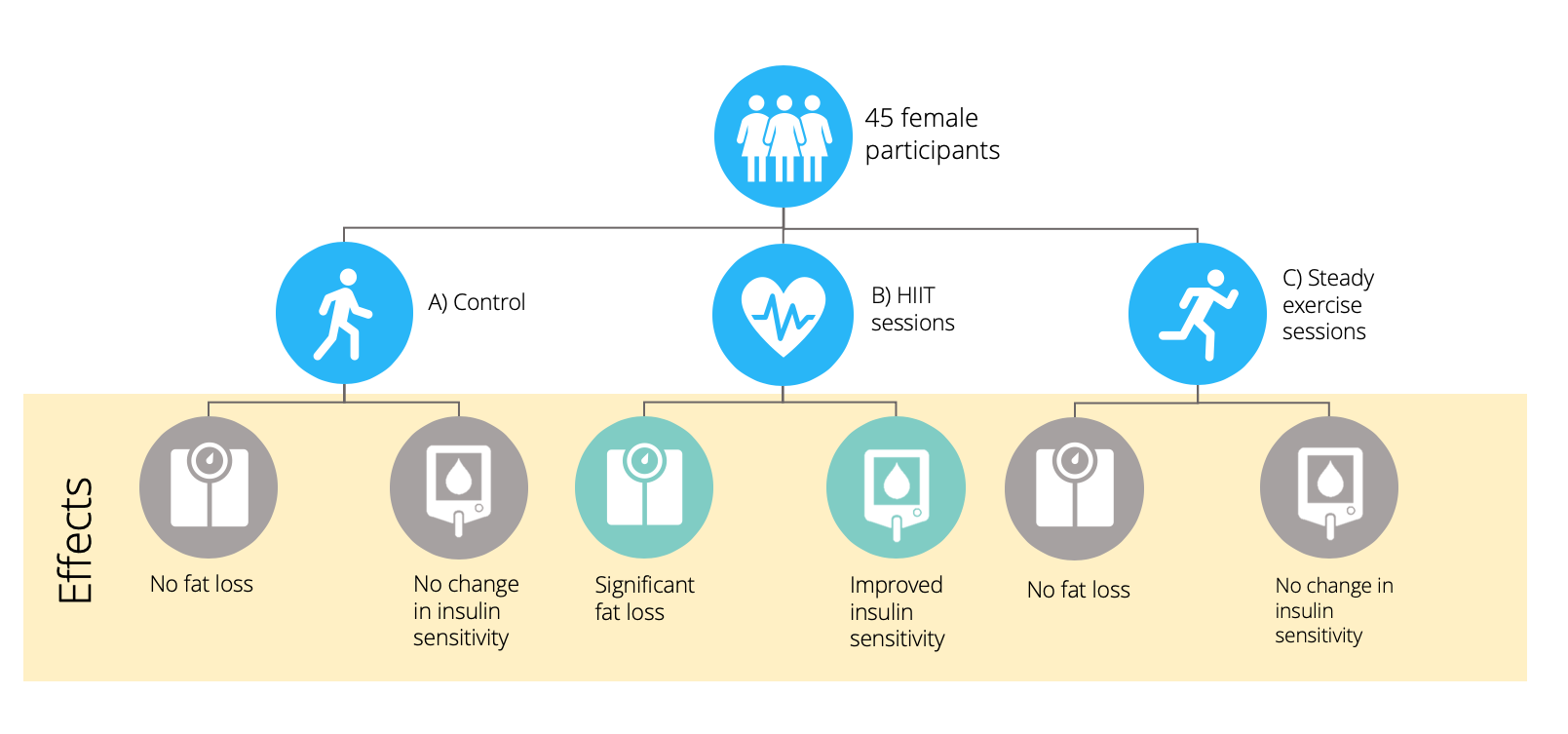

However, evidence suggests that high-intensity exercise promotes fat loss. One study controlled the participants’ diets and split them into high-intensity or moderate-intensity exercise groups.

The high-intensity group completed short bursts of exercise, whereas the moderate-intensity did longer, steady exercise sessions.

Results indicated that the shorter and high-intensity exercise sessions resulted in more fat loss.

The researchers suggested that high-intensity exercise positively impacts certain stress hormones released by the kidney that accelerate fat oxidation.

Having said that, finding the time to exercise is significant. Any form of exercise is beneficial for several reasons, including improved blood sugar control, mental health, and heart health.

Key points:

- Moving more doesn’t inherently lead to weight loss

- Short bursts of high-intensity exercise can promote fat loss more than moderate-intensity exercise.

- All types of exercise are beneficial for your overall health.

Take home message

- The ‘eat less, move more’ model suggests that if we simply take in less energy than we’re using, we will lose weight.

- This model does not account for the influence of mindset and environment on food choices and focuses primarily on willpower.

- Achieving a calorie deficit might work in the short term, but it’s challenging to stick to in the long term, and our bodies can respond by increasing our appetite.

- Not all calories provide equal health benefits.

- Refined carbohydrates can make us feel low on energy and spike our blood sugar, whereas proteins and fats leave us fuller for longer.

- Any exercise benefits our overall health, but exercise doesn’t inherently lead to weight loss.

If you’d like a 7-day NHS-trusted meal plan developed by our dietitians, click here.