Plenty of evidence demonstrates the benefits of exercise in delaying or preventing chronic health conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure.

It is also widely accepted that regular exercise can provide many indirect health benefits, such as weight loss and improved sleep.

As humans are living longer lives, there is a higher chance that our brains will age and our cognition (e.g. memory, thinking skills, speech) will decline. Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of Dementia, affects roughly 40-50 million people worldwide and is predicted to reach 82 million people by 2030.

‘Brain training’ technology, that promotes improved brain function, has become very popular. However, the evidence for this technology is lacking. A BBC-led trial trained individuals in specific tasks, designed to improve attention and memory, for 6 weeks and then tested their abilities. Results indicated that people demonstrated a modest improvement in the task they had been trained in, but this improvement was not transferred to other related tasks.

So if the evidence behind ‘brain training’ tasks is unclear, what can we do to keep our minds as sharp as possible? Research suggests that regular physical activity may help to slow the progression of cognitive decline.

The main brain areas of interest

The primary area of the brain that has been of particular interest to researchers is the hippocampus. The hippocampus is located within the area of the brain that regulates emotion and is primarily essential to learn new information, make memories, and have spatial awareness.

Many factors can influence the functionality of this brain region. Evidence suggests that stress and ageing, in particular, can shrink the size of your hippocampus, as well as other brain regions. The structural decline can begin as early as our 20s!

The second area of the brain that researchers are interested in is the prefrontal cortex. This area of the brain is mainly responsible for the organisation of behaviour, speech, and reasoning.

Does exercise impact these brain areas?

A randomised trial found that three sessions a week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (e.g. walking, cycling, or jogging) for 1 year increased the size of the hippocampus by 2%.

Is 2% a significant increase? When you consider that the hippocampus has been shown to reduce in size by around 1.5% each year after age 70, 2% is a notable difference. So it seems that exercise can slow the natural progression of hippocampus shrinkage. The same study also suggested that the fitter you are, the less likely it is that your hippocampus with reduce in size at a fast rate.

The same study also showed that higher fitness levels were protective against hippocampal volume reduction. Essentially, the fitter you are, the less likely it is that your hippocampus will shrink.

The suggested mechanism of this effect is down to a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF. BDNF promotes the growth and repair of nerve cells in the brain (neurons). Research demonstrates that exercise stimulates BDNF. This suggests, therefore, that exercise promotes the growth and repair of nerve cells in the brain.

Evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex also responds positively to exercise. A study randomized 59 healthy, less active volunteers aged 60-79, into 2 groups. Half into an aerobic training group, and the other half into a stretching group over 6 months. The aerobic training group showed a significant increase in prefrontal cortex volume.

Do the effects of exercise improve cognition?

As a reminder, cognition includes every-day brain activity that happens without thinking, such as memory, attention, and mood. Some cognitive decline is natural and part of aging, but can understandably cause mental health issues, such as depression.

As discussed above, exercise appears to change the volume of 2 important brain areas. The next question to ask is whether these changes influence cognition.

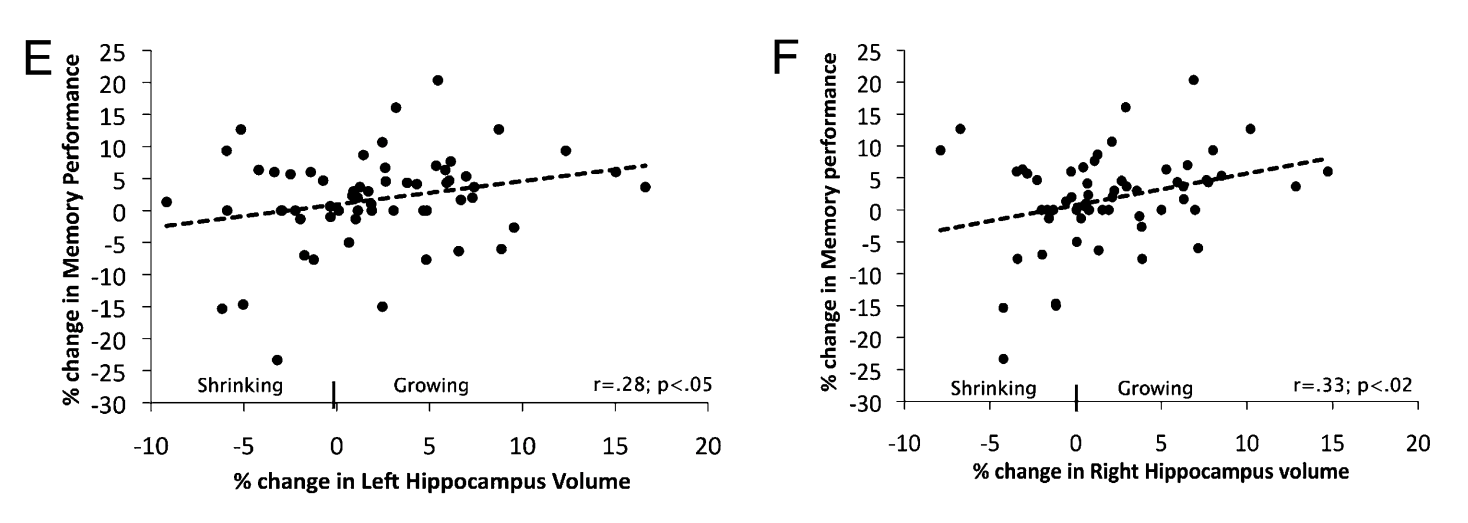

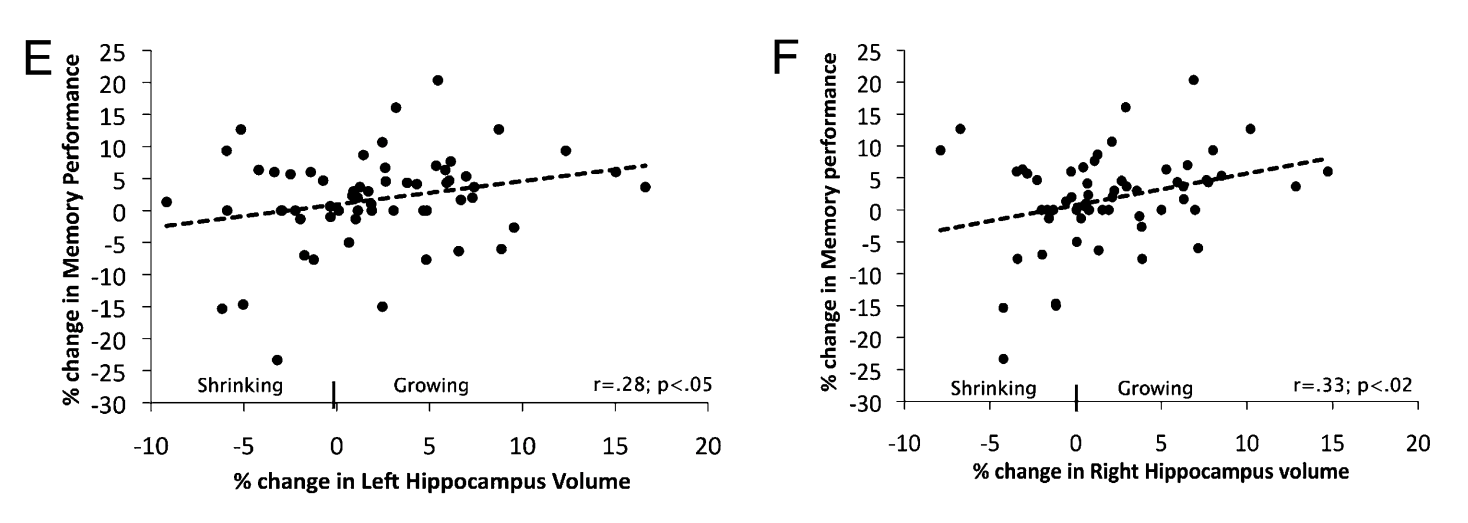

A study showed that an exercise-induced increase in hippocampal size was significantly linked to improvements in memory performance tasks of older adults (diagram below). This suggests that the changes seen in the brain as a result of exercise do, in fact, impact cognition.

Is it only aging brains that see this benefit?

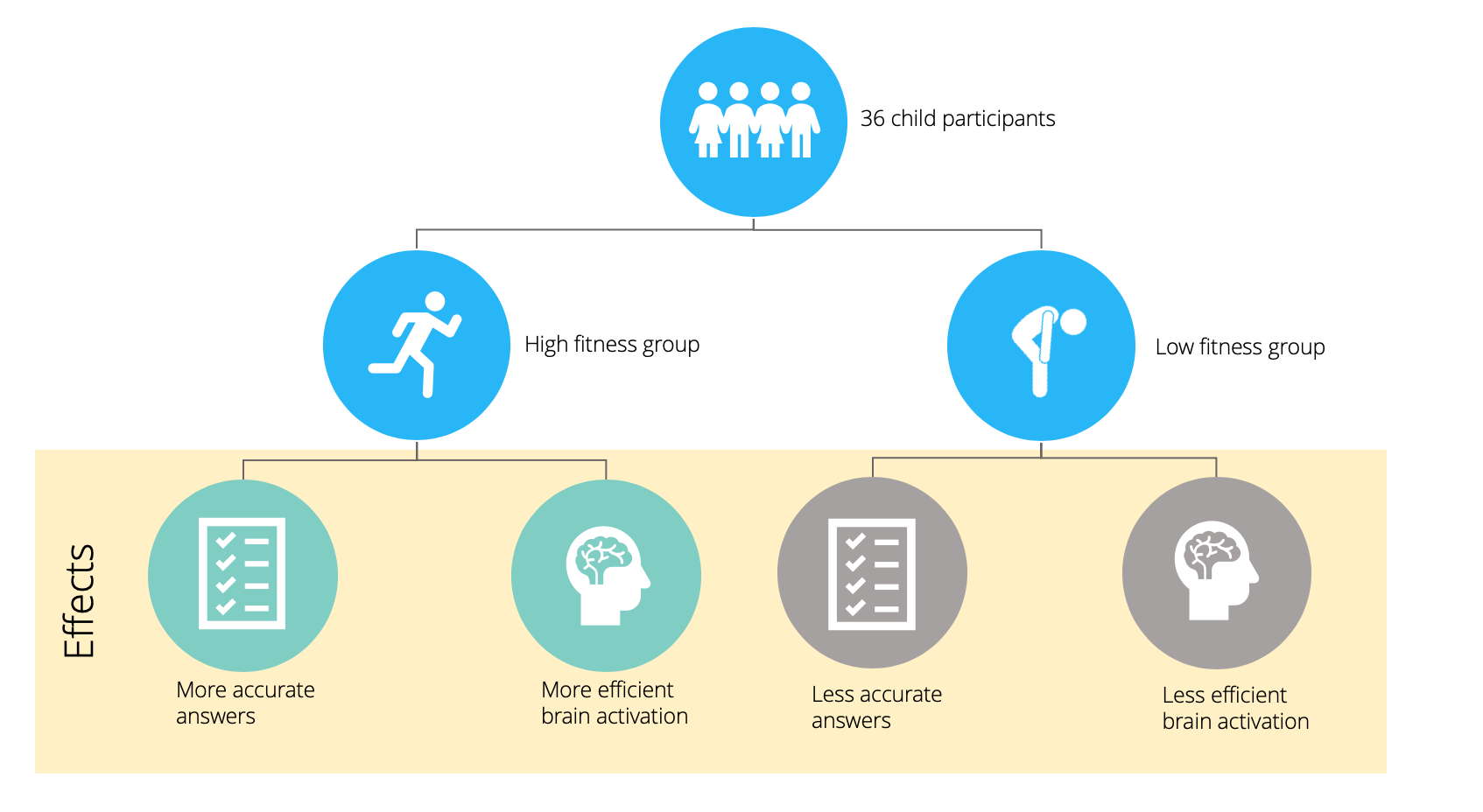

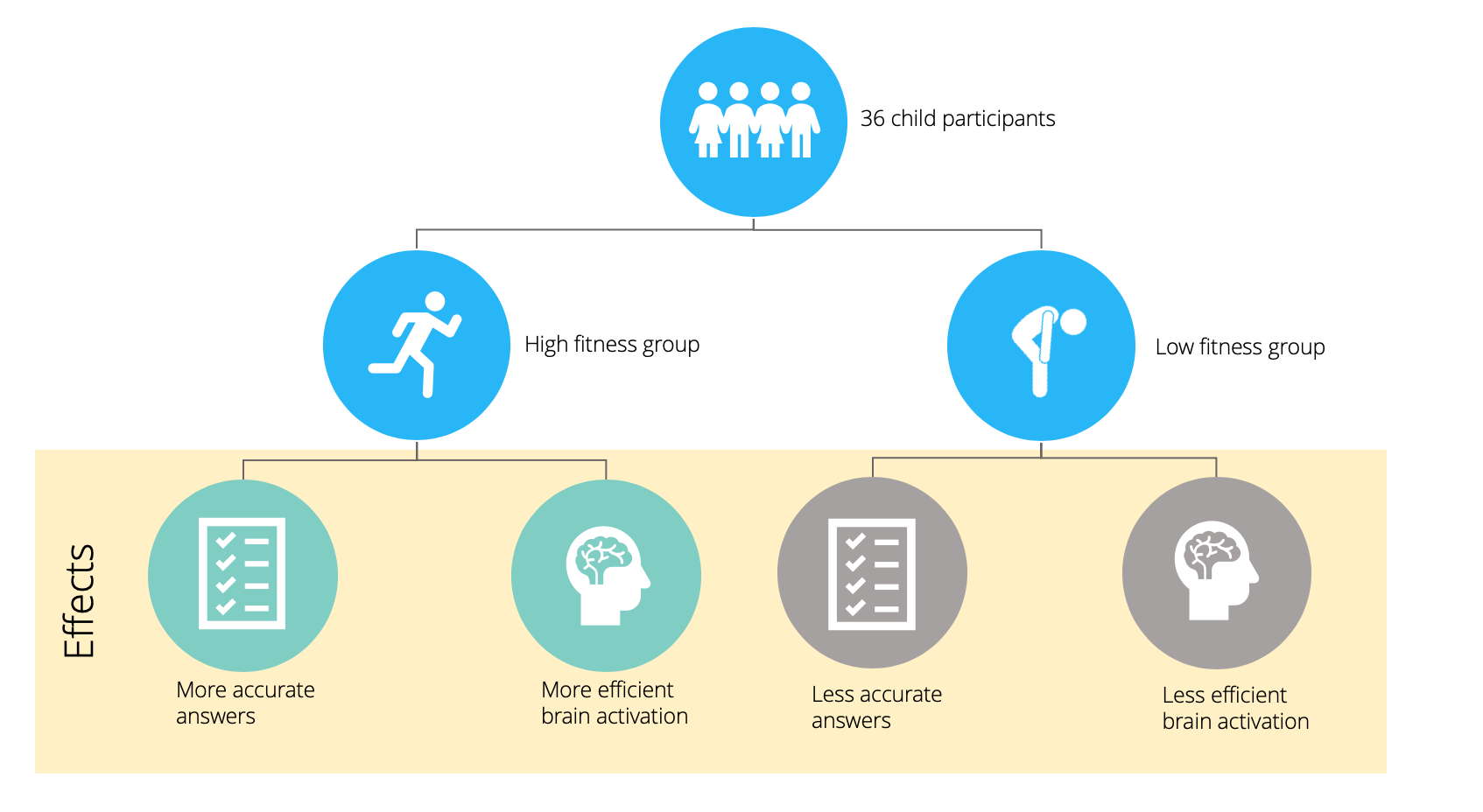

One study investigated the same relationship, between exercise and cognition, but in children. After completing an aerobic fitness test, 36 children (aged 8-10) were split into either a) high-fitness or b) low fitness groups. They then completed a cognition task while having a functional MRI brain scan.

There was a significant difference between groups a) and b) on task performance, with group a) performing better on the test. This suggests a positive link between the childrens’ fitness and cognitive function.

This is extremely important as aerobic fitness and good cognitive control has been strongly associated with academic performance. So it appears that exercise can benefit brains of all ages!

Does the type of exercise matter?

One study compared the impact of little activity, moderate exercise, and high-intensity exercise on participant’s ability to learn new material. The low activity group sat down for 15 minutes, whereas the moderate-exercise group completed 40 minutes of jogging, and the high-intensity group completed 2 3-minute sprints.

They measured their ability to learn new material a) immediately after, b) 1 week later, and c) 8 months later. There were minimal changes seen after 1 week and 8 months, but the high-intensity exercise group demonstrated a 20% increase in learning ability immediately after the exercise compared to the other groups.

Another study showed a significant increase in prefrontal cortex function, but not in hippocampal function, immediately after vigorous activity. This suggests that the prefrontal cortex benefits immediately from exercise as well as in the long term, whereas the benefit to the hippocampus is noticeable after long-term exposure to aerobic exercise.

So it seems that both moderate-intensity (aerobic) and high-intensity (anaerobic) exercise provide either long or short-term benefits to the brain, depending on the particular brain area. Perhaps finding the time to exercise should be a priority for us all!

Take home message

- Aerobic exercise benefits the structure of 2 important brain regions (the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex).

- These benefits seem to be strongly linked to improved cognition (memory, speech, attention).

- High-intensity exercise has an immediate positive effect on the prefrontal cortex, but a long-term positive effect on the hippocampus.

- There appears to be a strong positive link between fitness levels and cognitive function, for individuals of all ages.

- Exercise can delay the natural, negative impact of ageing on the brain, which is important to consider for elderly individuals who show any signs of cognitive decline.