In this article I’m going to discuss an incredibly compelling neuroscience model that’s relevant for all kinds of behaviours and perceptions, not just eating.

Knowledge of this model should provide insight, reassurance, and excitement about the power of knowledge for improving your daily decisions, habits, and personal growth.

Knowledge of knowledge

Over the eight years of running Second Nature, I’ve had debates with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people regarding the obesity and type 2 diabetes epidemic.

Namely around the question: what are the main drivers of the obesity epidemic?

Undoubtedly this is an extremely deep web of interconnecting drivers: genetic, environmental, societal, and individual.

But one driver that I’ve found often gets discounted is knowledge i.e. that knowledge isn’t a critical driver of the obesity epidemic.

Two common arguments against knowledge have been:

- “Most people know what they should do and eat; they just don’t do it”

- “If knowledge was a key problem, then we should have solved it already via the myriad of health and weight-loss books already out there”

In this article – continuing the broader theme of insights from Andrew Huberman – I’m going to argue why knowledge is critically important.

And more specifically: why it’s being aware of the right knowledge.

I appreciate there’s always going to be a level of subjectivity in the scientific field regarding what is ‘right’ vs ‘wrong’, but there are some aspects that are grounded with more robust scientific backing.

So, it’s about having knowledge of the right kind. For simplicity, let’s refer to it as knowledge of knowledge.

Who is Andrew Huberman?

Dr Andrew Huberman is a neuroscientist and professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology at Stanford University. In Jan 2021 he launched his podcast, which has taken off over the last few years, with over 1.5 million subscribers. However, the podcasts are quite long (2 hours+) and scientifically technical; so they aren’t the easiest things to unpack if you didn’t study a science degree or have a broader personal interest in the field of neuroscience.

In these series of Huberman-related articles, I aim to pull out the most interesting insights and concepts from his podcasts, and how they might relate to our daily lives.

What we should do vs what we actually do

I’ll articulate this idea using a model that Andrew Huberman discusses in episode 36 of his podcast.

As mentioned at the start – this model is relevant for all kinds of behaviours and perceptions, not just eating.

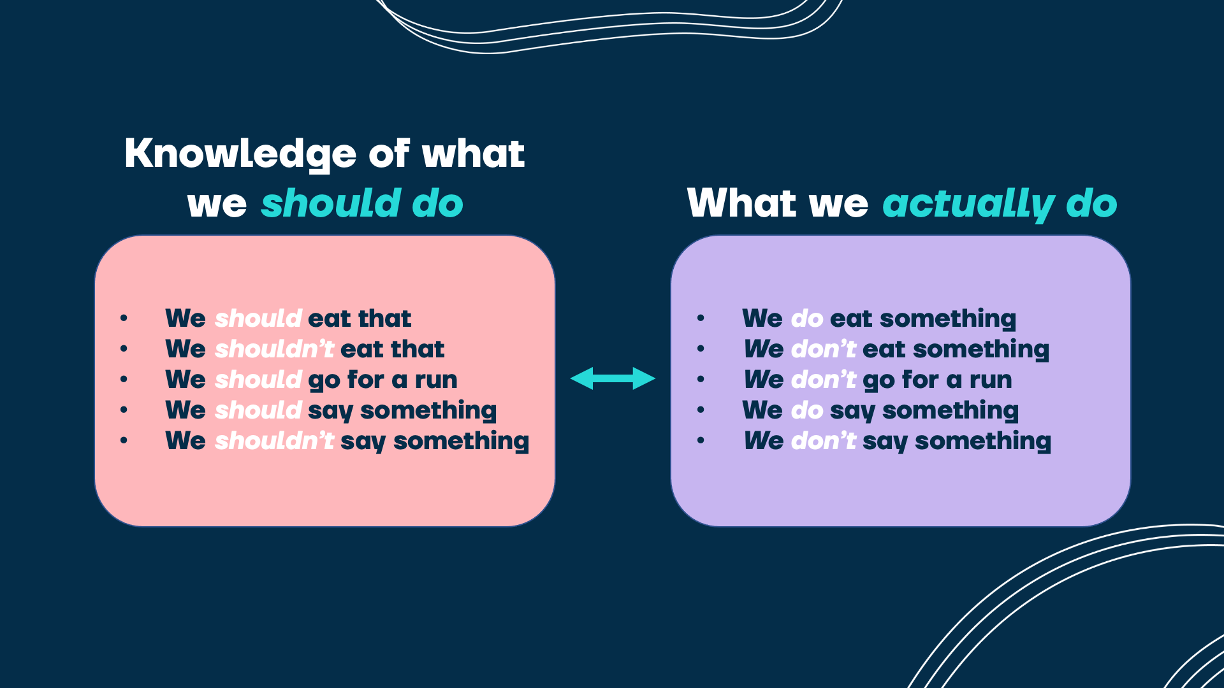

We start with two boxes: knowledge of what we should do vs what we actually do:

If you think about your own personal life and the decisions you make on a daily basis, there’s an interesting tension between these two boxes:

Why can we often ‘know better’ and not ‘do better’?

What’s intervening between those two boxes to influence our decisions?

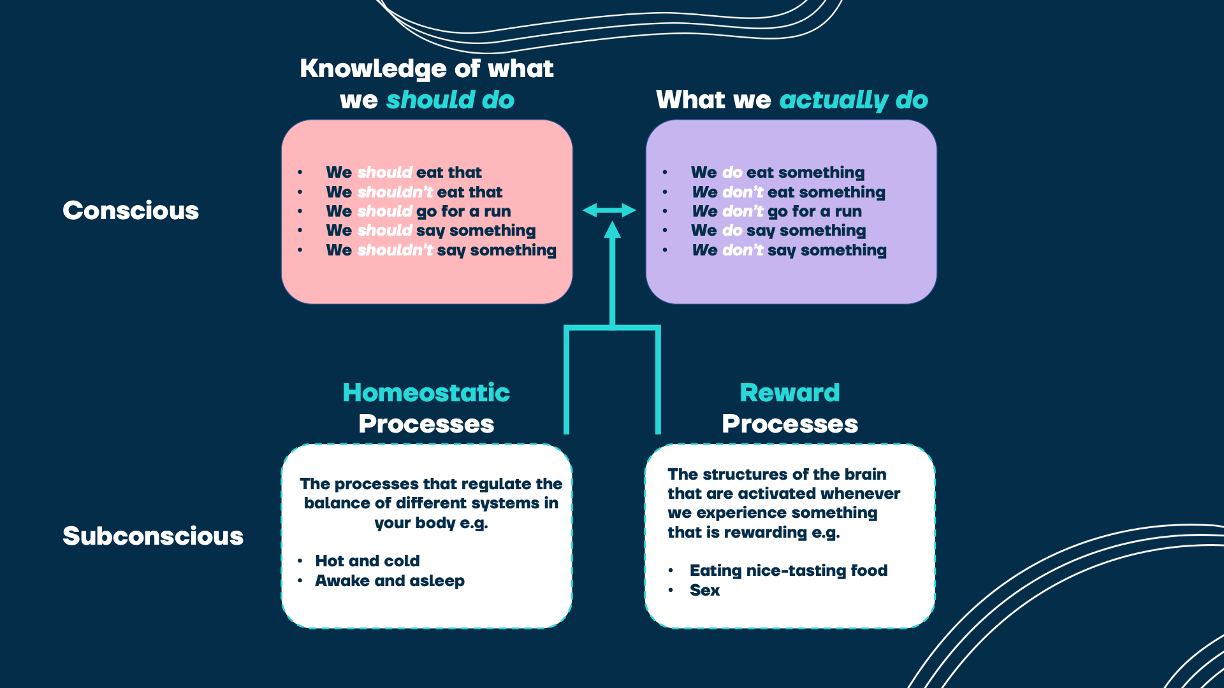

The answer is that there is another level below that is feeding into the gap between these boxes. These subconscious processes are homeostatic and reward processes.

These are strong subconscious processes that feed into the tension between what we should do vs what we actually do.

It also helps explain why we can find ourselves doing things that are not good for us, or for other people.

But there’s a positive, as Andrew Huberman surmises:

But fortunately, there is this great gift – which is that knowledge of knowledge can allow you to do better.

And, that knowledge of knowledge allowing you to do better over time leads to this incredible phenomenon called neuroplasticity – which is essentially translated into:

Doing better over time, even if difficult, eventually makes doing better reflexive (i.e. performed without conscious thought, much like a reflex)

Take Home Message

- When you think about the tension between what you should do vs what you actually do, take comfort in the fact that there are powerful subconscious processes influencing your decisions and actions.

- Fortunately, the knowledge of this (i.e. the knowledge of knowledge) can allow you to do better.

- Doing better over time, even if difficult, eventually gets you to a stage where these habits and behaviours become automatic.

So, if you’re struggling with implementing a new habit that you find particularly challenging – regularly exercising, cooking meals rather than ordering takeaways, going to bed earlier, drinking water instead of fizzy drinks – then persistence with these challenging habits will make them easier over time.

The key is to be aware of this, and to not give up.