Jump to: Reward-based learning | The role of dopamine | Placing certain food on a pedestal | Ideas for other rewards

Mind

Why we shouldn’t bribe children with food

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Here are 3 reasons why we shouldn’t bribe children with food:

- It encourages reward-based learning and reinforces this habit for the future

- It produces a dopamine release, leading to cravings for these food rewards

- It places food on a pedestal and gives certain foods a higher importance than others

Parents and carers are the most influential people in a child’s life and greatly impact a child’s eating habits.

When our children won’t cooperate, it’s common to turn to bribes or rewards to get them to carry out positive behaviours like finishing their greens, getting through a long car journey, or potty training.

We get it, sometimes it’s impossible not to bribe our children with food. When you’ve just got home late from swimming classes because of traffic, you’ve got 3 children all screaming for attention because they’re hungry, one of them has hurt their leg, and dinner it’s not ready, its totally fine to resort to whatever works in this situation and you shouldn’t feel guilty for doing so.

While it’s important to promote healthy habits around food and avoid using it as a reward, sometimes, using this might be the only tool we have available. This is ok, as long as we recognise the benefits and limitations of using food as a reward and do this responsibly.

What’s most important is to focus on having a variety of tools available so that we don’t rely only on using food as a bribe, and to remain calm and balanced in our approach to eating experiences.

If you want more tools to build a healthy relationship for your children, head to our free resources here.

Key point:

- While using food as a reward can be useful in certain situations, it should be approached with balance, as relying on food rewards regularly can have long-term implications on a child’s relationship with food

1) Reward-based learning

Our brain associates food with cues like places, thoughts, situations, feelings, or people.

To form an association, the brain lays down neural pathways so that when we’re exposed to a particular cue, we perform a behaviour automatically in response, and get a reward.

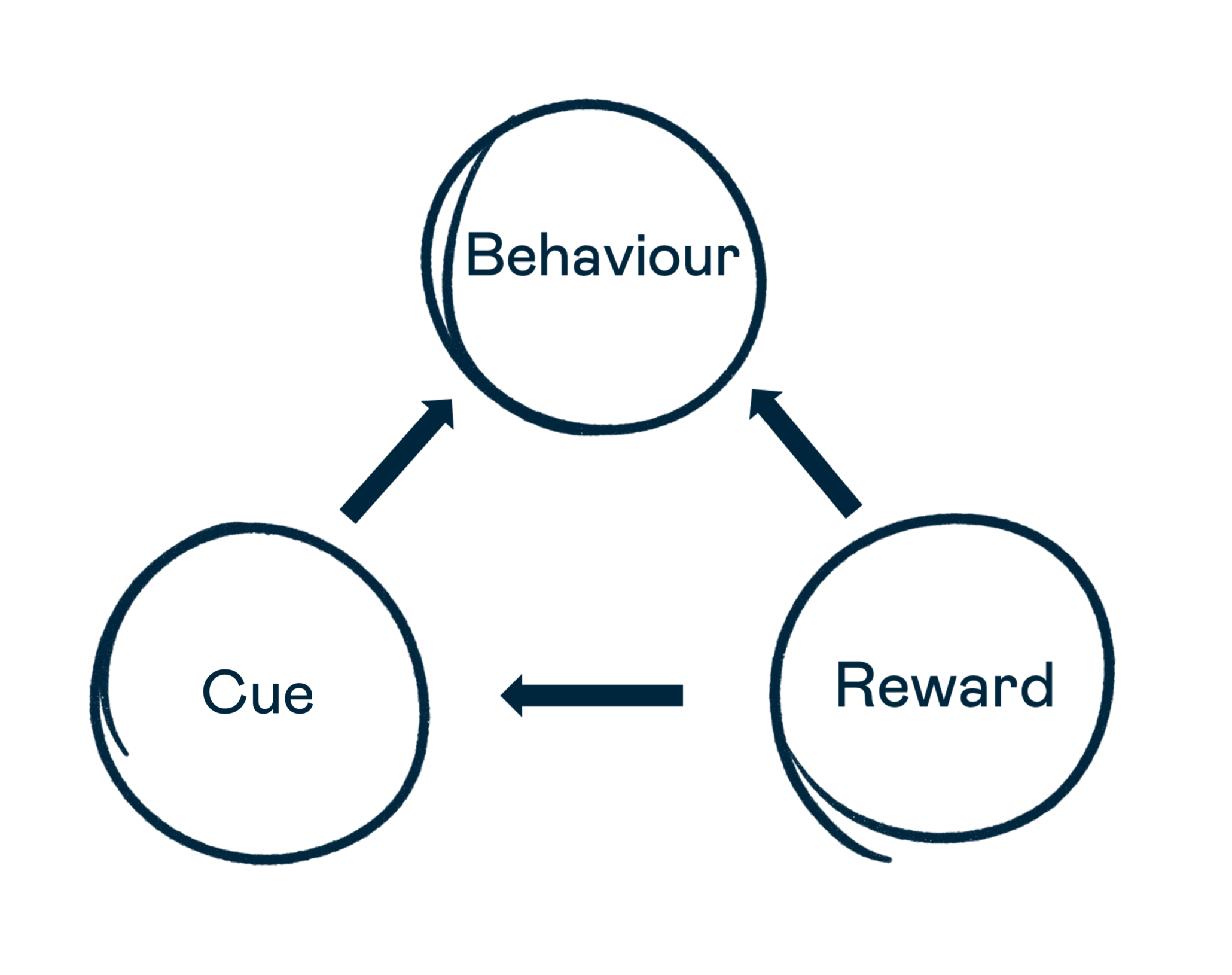

This learning cycle is known as ‘reward-based learning’. There are three basic elements: a cue, a behaviour, and a reward.

For example,

1) Cue: we see a piece of cake at a birthday party

2) Behaviour: we eat the cake

3) Reward: it tastes good and makes us feel good

In this scenario, our body sends our brain a message: ‘remember what you’re eating and where you found this’. This memory is now in our brain, so we repeat this process next time: ‘see the cake, eat the cake, feel good, repeat’.

The same can be applied when we use food as the ‘reward’ part of the cycle with our kids.

For example,

1) Cue: a child sees a vegetable on their dinner plate that they don’t like

2) Behaviour: the child eats the vegetable when we promise a reward at the end

3) Reward: the parent gives the child a piece of chocolate and the child feels good

When we reward a child for a behaviour, they associate the behaviour (e.g. eating vegetables) with the reward (e.g. a piece of chocolate), motivating them to do it more.

The more we repeat this process, the more it strengthens the neural pathway in the brain until it eventually becomes automatic.

So now, whenever they have something on their plate they don’t want to eat, they’ll expect a piece of chocolate as a reward.

Since food provides a strong sense of reward to the brain, particularly ultra-processed and high-sugar foods, often these associations can develop quickly.

Key points:

- The brain associates food with cues like thoughts, situations, feelings, or people through reward-based learning, which involves a cue, behaviour, and reward

- When we reward a child for a behaviour, they associate the behaviour (e.g. eating vegetables) with the reward (e.g. a piece of chocolate), motivating them to do it more

- The more we repeat this process, the more association strengthens until it becomes automatic

2) The role of dopamine

Eating food gives our brains (and our children’s brains) a sense of reward. One chemical messenger released in the brain in response to food is called ‘dopamine’.

Dopamine is released when we expect a reward and drives us to engage in pleasurable activities like shopping, seeing friends, listening to music, etc.

Dopamine is sometimes mistakenly referred to as our ‘feel good’ chemical messenger, but its key role is actually motivation and learning.

When we give children food as a reward, dopamine reinforces this learning to make their brains realise that the reward is a pleasurable activity.

This realisation then motivates them to go back for more of the same thing, in other words, eating more of that food.

The next time they see or think about that food, their dopamine levels will increase, and they’ll be motivated to have it again.

Regularly giving children these food rewards will encourage children to crave them, even without the cue or behaviour.

Considering that the foods we use as rewards are often less nutritious, higher in sugar, and more processed, overeating these foods increases the risk of weight gain and weight-associated diseases.

Key points:

- Dopamine is a chemical messenger in the brain released in response to rewards and plays a key role in motivation and learning

- When we give children food as a reward, dopamine reinforces this learning, motivating them to eat more

- The foods we use as a reward are often less nutritious, high-sugar, and processed foods. Overeating these foods increases the risk of weight gain and weight-related diseases.

3) Placing certain foods on a pedestal

The foods we use as a reward will also become more appealing than those that aren’t. They might be seen as ‘off-limits’ unless given as a reward, which can create a food hierarchy in children’s minds and make them want that food more.

For example, if a parent always bribes a child with ice cream, but at no other time does the parent give the child ice cream, the child will start to see ice cream as a more appealing food because it’s restricted and only allowed when being rewarded.

It’s the ‘forbidden fruit’ effect – they’ll want it more because they can’t have it often.

On the other hand, the foods that aren’t given as a reward will become ‘boring’ and ‘unappealing’, and children may be less willing to eat these foods without a reward. For example, vegetables and fruits.

This approach seems counterintuitive for promoting a nourishing diet and fostering a positive relationship with food, as often the ‘boring’ or less appealing foods offer more nutritional value.

If you notice that you’re rewarding yourself with food, we address this specific topic in our new course on Developing a healthy relationship with food. Join us to change the way you see food.

Key point:

- Using food as a reward can create a food hierarchy in children’s minds. Reward foods become more appealing and non-reward foods become less appealing.

Healthy ways to reward children

Sometimes, bribing or rewarding children might be the only way to get them to carry out new, healthy behaviours. This is ok, but instead of relying on food rewards, try using some non-food rewards.

Here’s a list of non-food rewards to try with your children:

- Organising a play date for them

- Making them laugh

- Reading a book together

- Listening to their favourite song

- Playing a game with them

- Building a den outside in the garden

- Giving them new craft supplies, like paint or colouring pens

- A trip to the play park

Another way to avoid using food as a reward is to encourage mindful eating practices. We’ve got a detailed guide on how to do this with your children, which you can find here.

Take away messages

- Using food as bribery or reward with children might seem like a helpful tactic in the moment, but can have long-term implications on a child’s relationship with food

- The ‘reward-based learning’ cycle explains how our brains create associations between certain cues, foods, and rewards. There are three basic elements to this cycle: a cue, followed by a behaviour, followed by a reward.

- Suppose we reward a child for behaviour often. In that case, they start associating the behaviour (e.g. eating vegetables) with the reward (e.g. a piece of chocolate), which motivates them to do it more. They’ll expect the reward when exposed to the cue or carrying out the behaviour.

- Eating gives our brains a sense of reward. One chemical messenger released in the brain in response to food is called ‘dopamine’. When we give children food as a reward, dopamine reinforces this learning, which motivates them to go back for more.

- The foods that we use as a reward will also become more appealing than foods that aren’t. This is counterintuitive for promoting a nourishing diet as often food rewards are less nutritious and more processed.

- We know that sometimes bribing or rewarding children are the only way to get them to carry out new, healthy behaviours, but we’d recommend trying not to use food. If you need some ideas of non-food rewards, look at our list in the guide.

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Download our free, indulgent 7-day meal plan

It includes expert advice from our team of registered dietitians to make losing weight feel easier. Subscribe to our newsletter to get access today.

You might also like

As seen on

As seen on